To make it you will need:

– materials: 1

.

A sheet of polystyrene foam 2.5 - 3 cm thick (other sizes vary, but the standard sheet is approximately 50 * 100 cm, there are also larger ones). I used two pieces of foam from the furniture box, measuring 50*15*2.5 cm. 2

.

A mop stick with a length of at least 130 cm (note that the excess plastic parts will most likely need to be removed and the stick will become shorter) or a stick for a curtain rod (they are usually a very beautiful color of noble bronze, but the metal there is quite thick and therefore the product may be too heavy and the risk of its breakage will increase, and this cornice is not cheap). 3

.

A roll of masking tape/tape (preferably two – one 50 mm wide, the second 20-30 mm). At the same time, I recommend using not paper-based tape (usually light yellow), but tape that looks like thin plastic - it stretches easier and is itself much denser. If you have paper masking tape, then it is better to take it with a reserve (two wide rolls and one narrow). 4

.

A roll of double-sided tape. It’s also better to take two – 50 mm and 20 mm wide, because a wide one is very inconvenient to cut lengthwise. 5

.

Stationery pins such as nails - 100 pcs or the same number of wallpaper nails with a length of at least 1 cm. 6

.

A roll of simple wood-look wallpaper, like a “country fence.” You choose the color at your discretion. I had the most common ones - the colors “stalled wood”. If you find a more noble shade, take it. In reality, you will need about two meters, so if you have the rest lying around somewhere, use it. The texture of the wallpaper is preferably the most ordinary - no embossing, etc. 7

.

A roll of food foil (5 meters is enough even taking into account all the unsuccessful experiments) 8

.

A piece of cardboard “metal-like” 20*15 cm. If you don’t have it, you can do without it. Or use a disposable foil plate (it will have to be flattened into a leaf using improvised means - from a liter jar to a rolling pin). 9

.

About 1 meter of thin wire - insulated, but preferably copper, because... Aluminum will most likely break. 10

.

About 20 paper clips. – tool: 1

.

Stationery scissors, whatever you like (the glue that sticks to the blades when cutting the tape is very difficult to wash off) 2

.

A breadboard knife (one with a retractable blade, preferably durable) 3

.

Pliers (if not, you can make do) 4

.

Hands from the right place 5

.

Vacuum cleaner (optional) 6

. Large flat blade screwdriver (optional)

Manufacturing stages:

We hope you find it useful, your editors.

If we say that the musket is the progenitor and the main archetype of muzzle-loading weapons, it will sound very plausible. The appearance of the musket on the battlefields of the Middle Ages turned the rules of warfare upside down and sent the most famous warriors of that time - the knights - into oblivion. If we ignore the fact that this was by no means the very first small arms, the shotguns and rifles of our time owe their existence to it alone.

late 17th century musket

Principle of operation

The operating principle of the musket mechanisms is based on the use of a lock-type trigger mechanism, which was the founder of all subsequent methods of igniting a powder charge. Due to its low cost, the matchlock mounted on a musket dominated in Europe until the invention of the first flintlock guns.

wick lock

The ignition of the gunpowder occurred due to the interaction of the trigger coupled with the smoldering wick and, in fact, the gunpowder charge. It is not difficult to imagine that such weapons had a number of significant disadvantages:

- the wick had to be kept smoldering;

- the need for constant access to fire;

- problems of combat in conditions of high humidity;

- problems with camouflage in the dark - the light from the wick gave away the shooter’s position.

A musket is a single-shot weapon. As a result, after each shot it was necessary to charge it again. Thus, having fired a shot, the shooter poured a pre-measured portion of gunpowder into the barrel of the weapon, pressed it with a wad and a cleaning rod, added another bullet (a ball of lead) to this mixture and fixed it with another wad. This kind of manipulation made it possible to fire about one shot per minute.

The musket's aiming system included only a barrel and a front sight - there was no rear sight at that time.

In order to avoid inaccuracies in terminology, it is worth noting that the concept of a musket and a gun takes into account only the length of the barrel of a firearm, while their design and everything else is of a secondary nature. For example, the famous "Winchester 1873", released in conjunction with a specially designed unitary cartridge, had a rifled barrel and was produced as a carbine, shotgun and musket, which had different barrel lengths.

Basic performance characteristics of a musket (

17th century)

The musket of the late 17th century had the following characteristics (performance characteristics):

- caliber – 17-20 mm;

- barrel length – 900-1000 mm;

- total length – 1300-1450 mm;

- weight – 4-6 kg.

There is probably no person who has not at least once heard the word musket, and even more so the word “musketeers” derived from this weapon. By the way, this word has brought historical confusion to humanity. Thanks to the writer Dumas and his musketeers, humanity has taken root in the misconception that France is considered the birthplace of muskets, but these firearms were not invented by the French, although later they had a hand in the musket in terms of its improvement.

How did the first muskets appear?

In the mid-16th century, a firearm called the arquebus arose, which can be considered the ancestor of the classic musket. For some time, arquebuses were considered a formidable weapon, but it soon became clear that the arquebus was an unreliable weapon. The bullets fired from the arquebus, due to their low weight (no more than 20 grams), as well as their modest caliber, were powerless against enemy chain mail and armor, and loading the arquebus was a long process. It was necessary to invent new, more effective firearms.

And such a weapon was invented. History assures us that the first long-barreled gun with a wick-lock, later called a musket, appeared in Spain. History has preserved the name of the gunsmith who invented the musket. This is a certain Mocheto, who lived in the Spanish city of Veletra.

The first musket had a long barrel - up to 150 cm. Thanks to the long barrel, the caliber of the musket also increased. The new gun was able to fire new charges with a larger amount of gunpowder, which allowed the bullet to fly further and at greater speed, resulting in a greater stopping power for the bullet. Such a bullet could no longer be stopped by chain mail and armor.

The first samples of muskets were quite heavy (up to 9 kg), and therefore it was difficult to carry them - the muskets were fired from previously prepared positions. And still, shooting from them was not an easy task: when firing, the musket had a strong recoil, and loading it required time and skill. Soldiers of European armies armed with muskets (primarily Spain, Germany and France - as the most powerful powers of the Middle Ages) represented a formidable force.

Features of the combat use of muskets

The main operation of weapon mechanisms is associated with the use of a firing mechanism. The appearance of the lock gave impetus to the emergence of all subsequent types and methods of igniting the charge in hand-held firearms. Despite the relative simplicity of the design, matchlock guns remained in service with European armies for a long time. This method of activation was far from perfect. All matchlock guns have the same disadvantages:

- the wick must always be kept in a smoldering state during the battle;

- with the musketeer ranks there was a special person responsible for the source of open fire;

- the wick is highly susceptible to high humidity;

- lack of camouflage effect in the dark.

The shooter equipped his gun with a charge of gunpowder, pouring it through the barrel. After which the gunpowder was compacted in the breech of the barrel. Only after this a metal bullet was inserted into the barrel. This principle has not changed for almost two centuries. Only the advent of paper cartridges simplified the situation on the battlefield a little.

Individual parts of the musket, such as the stock, called the fourchette, the butt and the firing mechanism, have remained unchanged. The caliber has changed over time and has been slightly reduced. The design of the trigger mechanism has also changed. Since the mid-17th century, battery locks of the Le Bourgeois system have been installed on all firearms. In this form, the musket survived until the era of the Napoleonic wars, becoming the main weapon of the infantry. The fastest to switch to new types of weapons were private armies, filibusters, corsairs and robber gangs. Muskets with a battery lock were much more convenient to use and in battle.

Pirates are credited with using shot charges to fire muskets. Thus, it was possible to significantly increase the destructive effect of the shot. A double-barreled musket with shortened barrels that fired shot became a deadly melee weapon. During a boarding battle, it was not necessary to hit the target at a great distance. A distance of 35-70 m was sufficient for effective fire. Armed with pistols and blunderbuss (a shortened version of the musket), pirate crews could successfully resist even military vessels, as evidenced by numerous historical factors. The ship's rigging was disabled by shotgun blasts from muskets, after which it was boarded by assault teams.

Blunderbuss could be easily recognized by their flared barrel. Some models used in naval battles did not have a stock and were adapted for shooting from the knee. Shooting shot charges from a distance of 20-30 meters, the blunderbuss was very effective in battle. Another advantage of this type of firearm is the loud effect of the shot. Short-barreled muskets made a thunderous sound when fired, producing a stunning psychological effect on the enemy. In addition to pirate ships, such guns were required to be on board each ship in case of suppression of a mutiny by the crew.

How to load a musket

Each of us has probably seen in films exactly how muskets were loaded. It was a long, complicated and tedious procedure:

- They loaded the musket through the muzzle;

- Gunpowder was poured into the barrel in the amount necessary for the shot (according to the shooter). However, in order not to make a mistake in the dose of gunpowder during the battle, the powder doses were measured in advance and packaged in special bags called chargers. These same charges were attached to the shooter’s belt during shooting;

- First, coarse powder was poured into the barrel;

- Then finer gunpowder, which ignited more quickly;

- The shooter pushed the bullet into the table with the help of a ramrod;

- The charge was pressed against a constantly smoldering wick;

- The ignited gunpowder threw a bullet out of the barrel.

It was believed that if the entire charging procedure takes no more than two minutes, then this is wonderful. In this case, it became possible to fire a salvo first, which often guaranteed victory in the battle.

Features of fighting with muskets

A warrior armed with a musket was called a musketeer. A bullet fired from a musket could win a battle, which, in general, was what happened. When firing from muskets in one gulp, it was possible to lay down a whole line of the enemy at a distance of up to 200 meters. The weight of musket bullets could be 60 grams. Armored knights were knocked out of their saddles with musket bullets.

Still, firing a musket was not an easy task. It took a long time to load the musket. The recoil when firing was such that it could knock the shooter off his feet. To protect themselves, the shooters wore special helmets and also tied a special pad to their shoulder. Due to the difficulty of shooting, there were two people with the musket: one loaded the weapon, the other fired, and the loader supported him so that the shooter did not fall.

In order to make it possible to fire muskets faster, the armies of many countries came up with various tricks. One of these tricks that history has preserved was the following. The musketeers lined up in a square consisting of several ranks. While the first rank was firing, the rest were loading their muskets. Having fired, the first line gave way to another, with loaded guns, and that one to the third, fourth, and so on. Thus, musket fire could be carried out constantly.

In the 16th century, during a battle, musket shooting was the decisive condition for victory. Often the side that was the first to fire a volley at the enemy won. If the first salvo did not give a decisive result, then there was no time to fire the musket again - everything was decided in close combat.

How to make a blade and assemble a sword or dagger at home?

A sword made by yourself can become an excellent interior decoration and the pride of its owner.

Features of a knife made from a spring

The popularity of spring steel knives is explained by their availability and low cost. The material has the characteristics necessary for high-quality blades:

- plasticity;

- viscosity;

- resistance to shock loads;

- hardness;

- wear resistance.

Most often, a knife is made from spring steel grade 65G, less often from 50KhGSA and 50KhGA. Minor differences in the characteristics of metals do not affect the quality of the blade. Regardless of the brand, spring steel lends itself well to heat treatment. Disadvantages include susceptibility to corrosion.

Double-barreled musket: the history of its appearance

In order to get out of the situation, it was necessary to somehow increase the rate of fire of the musket. However, rapid firing of muskets with a matchlock was impossible. The matchlock musket, due to its design, simply could not fire quickly. It was necessary to invent some new musket that could be fired faster.

The double-barreled musket was invented. The advantage of a double-barreled musket over a single-barreled one was obvious: instead of one shot, it could fire two, that is, shoot twice as fast. It was a kind of weapons revolution, but for unknown reasons the double-barreled musket could not take root in the infantry units of European powers. By the way, it is the double-barreled musket that is the progenitor of our hunting rifle - continuity through the centuries.

Pirate musket - the prototype of a modern pistol

But the double-barreled musket, like the single-barreled one, aroused interest among pirates of the 16th century. In subsequent centuries, until the 19th century, when muskets were replaced by more advanced weapons, and the pirates themselves for the most part sank into historical oblivion, pirate enthusiasm for this did not diminish at all. It was the pirates who, first of all, had a hand in improving muskets and contributing to the appearance of the first pistols.

Unlike the army, the “knights of fortune” were the first to fully appreciate what firearms are, and what advantage they give to those who own them and know how to handle them. Heavy musket bullets could easily disable a merchant ship, making it easy prey for filibusters. In addition, in hand-to-hand combat, a pirate armed with a musket was a very formidable combat unit.

To make it more convenient to shoot from a musket and carry it with them, the pirates thought about improving it. The French sea robbers were the most successful in this. They were the first to think of making the musket barrel shorter, reducing its size and caliber, and equipping the weapon with a handle resembling a pistol grip. The result was an easy-to-handle musket, which became the forerunner of modern pistols and revolvers.

The pirates nicknamed certain versions of the shortened musket blunderbusses. They differed from ordinary muskets in their shortened appearance, as well as the expansion at the end of the barrel. Blunderbuss could fire shotguns and hit several enemies at once. In addition, blunderbusses had a very loud sound when fired, which had a frightening psychological effect on the enemy. By the way, not only pirates, but also civilian ships of that time were equipped with muskets and blunderbuss to suppress mutinies on ships.

Homemade firearms

Homemade firearms

are made at home, most often illegally. It is distinguished by a variety of devices and technological solutions, from extremely primitive to (rarely) fully functional samples comparable to serial ones.

The quality of homemade shooting guns can vary greatly. First of all, it depends on the availability of the necessary tools and skills of the manufacturer, as well as on his aspirations. Homemade designs vary from the most primitive, repeating the first wick muzzle-loading pistols and shotguns, to quite advanced or even carrying new, never used technical solutions. In a number of countries, for example in China, where it is almost impossible to get factory-made weapons, the production of handicraft weapons is on a large scale [1].

Typically, such weapons are of rather low quality and are characterized by inaccurate shooting; the bullet is characterized by instability of trajectory, but this same circumstance, in addition to reducing accuracy, can lead to an increase in the stopping effect of the bullet.

Content

Samopal [edit | edit code ]

The simplest homemade firearm is a muzzle-loading samopal or “arson” (also arson

,

arson

, etc.). It refers to single-shot ramrod-type pistols. As a rule, a primitive ignition consists of a barrel made of a metal tube, plugged in some way - riveted, wrapped, filled with lead, welded (when filled with lead or plugged with a screw, the plugs are sometimes shot directly into the eye of the aiming shooter) from the treasury, and a wooden (less often plastic, textolite) stock. A seed hole with a diameter of 1.5-2 mm is made from the breech of such a barrel to ignite the propellant charge. The charge used is ground match heads, mixtures with potassium permanganate, or black powder. The projectile used is shot or bullets cast from lead. The barrel is tied to the handle with wire or attached in another accessible way. Ignition of the propellant is carried out using a match (sometimes several, for the sake of reliability) attached to the seed hole. Despite their structural simplicity and unprepossessing appearance, ramrod pistols have sufficient destructive power to cause serious bodily harm, and if a projectile hits vital organs, death. With a muzzle energy of more than 300 J and a caliber of more than 10 mm, the recoil of the weapon due to insufficient mass can cause injury to the hand. The range of accurate shooting at a 50x50 cm target does not exceed 5-7 m. Due to the unreliability of the design, as well as from an excess powder charge or wad, the ignition sometimes explodes in the hands, maiming or even killing the shooter.

Homemade products for a unitary cartridge [edit | edit code ]

More structurally complex examples of homemade weapons, as a rule, are manufactured for widely used cartridges. First of all, these are freely sold mounting cartridges, easily accessible cartridges for hunting smoothbore weapons, as well as 5.6 mm sporting and hunting cartridges. To manufacture such weapons, a fairly extensive set of equipment and metalworking tools is required, including at least a lathe.

Homemade products chambered for a unitary cartridge can be single-shot or multi-shot. The latter are divided into self-propelled guns with manual reloading, self-loading and automatic. Single-shot self-propelled guns are most often weapons with a “breakable” barrel. Locking occurs using a frame, a spring-loaded striker or a massive trigger. The trigger is usually quite primitive; it only ensures that the hammer or firing pin is de-cocked. The complete reloading cycle of such self-propelled guns is carried out by the shooter. Sometimes such self-propelled guns are disguised as familiar, unattractive objects, such as stationery pens, umbrellas, gear levers (in cars), canes, etc.

Multi-shot homemade guns have a magazine, a drum, or several barrels. Weapons where reloading is carried out using the muscular strength of the shooter include pistols with a rigid bolt lock and revolvers. Most often they have a single action trigger, although double action is also found on revolvers. Revolvers are usually copied from gas revolvers, which are unsuitable for conversion due to the fragile frame alloy. Self-loading and automatic pistols in most cases are built on the simplest principle of blowback. These are pistols, which are, as a rule, copies of gas pistols, and submachine guns, imitating the simplest examples from the Second World War, for example, “Stan”. All of the homemade products listed above can have both smooth and rifled (as a rule, low-quality or factory-made) barrels, although for point-blank distances, shooting accuracy and bullet stabilization do not play any role. There are products with a removable (less often integrated) muffler.

Forensic practice knows more than one example when serious crimes were committed using homemade weapons: robbery, causing grievous bodily harm, murder. The most famous case in the Soviet period was the gang of Tolstopyatov brothers, which operated in Rostov-on-Don in 1968-1973, equipped with homemade submachine guns and revolvers of an original design. There is also a known case in Omsk, where a mentally unstable Andrei Kudla used a homemade pistol to kill two people and seriously wound two more people [2].

At one time, large-scale handicraft production of weapons began in the Philippine city of Danao (English) (Russian (suburb of Cebu). The weapons industry in this city arose a long time ago: local residents made arquebuses for the Spaniards for centuries. During the Second World War, they produced weapons for the Japanese and Americans. After gaining independence, local gunsmiths switched to working for the mafia. The authorities struggled with this for many years and eventually came to a compromise: the craftsmen make weapons for ordinary citizens and the police, and the authorities in return provide them with workshops for work [3].

Further improvement of the musket

Meanwhile, the authorities of the leading European powers were not asleep. Their gunsmiths also began to think about improving the musket. Several European powers have achieved impressive results in this matter.

The Dutch were the first to succeed. Their craftsmen designed lighter muskets. Troops armed with such muskets were more mobile, and the muskets themselves became easier to fire. In addition, the Dutch improved the musket barrel by producing musket barrels from soft steel. As a result, musket barrels no longer exploded when fired.

German craftsmen also made a significant contribution to the improvement of the musket. They improved the firing mechanism of the musket. Instead of the matchlock method of shooting, the flint method appeared. The flintlock gun, which replaced the matchlock, was a revolution in the development of weapons in medieval Europe. The lever in the wick mechanism was replaced by a trigger, which, when pressed, released the spring with the flint, the flint hit the arm, resulting in a spark being struck and igniting the gunpowder, which, in turn, ejected the bullet from the barrel. It was much easier to shoot from a flintlock than from a matchlock.

The French were not far behind. First, they changed the butt of the musket: it became longer and flatter. Secondly, they were the first to equip muskets with bayonets, as a result of which muskets could be used as edged weapons. Thirdly, they installed a battery lock on the gun. Thus, the French musket turned into the most advanced firearm at that time. As a result, the flintlock gun replaced the matchlock. In fact, it was Napoleon’s army that was armed with French flint muskets, as well as the Russian army that opposed it.

The main parts of the musket remained unchanged until the very end of its existence. Some individual parts were modified at different times, but the principle of operation itself did not change. This applies to such parts as the butt, stock, working mechanism.

Musket used by pirates

During the era of colonial wars, when the Spanish fleet dominated the sea, muskets, along with pistols and arquebuses, became mandatory weapons on a ship. Handguns were greeted with great enthusiasm in the Navy. Unlike the army, where the main emphasis was on the actions of infantry and cavalry, in a naval battle everything was decided much faster. The contact battle was preceded by preliminary shelling of the enemy from all types of weapons. Firearms played a leading role in this situation, coping with their task perfectly. Artillery and rifle salvoes could cause serious damage to the ship, rigging and manpower.

Read also: How drying is done in production video

The muskets did their job perfectly. A heavy bullet easily destroyed the wooden structures of the ship. And close-range shooting, which usually preceded a boarding battle, turned out to be more accurate and crushing. The double-barreled musket came in handy, by the way, doubling the firepower of the naval teams. It is this type of weapon that has practically survived to this day, representing a hunting rifle with two barrels. The only difference is that modern shotguns are loaded by breaking the frame, while muskets were loaded only from the barrel. On muskets, the barrels were located in a vertical plane, while in hunting rifles a horizontal arrangement of barrels was adopted.

It is not for nothing that this type of weapon eventually took root in the pirate environment, where boarding combat was carried out over short distances and there was physically not enough time to reload the weapon.

It should be noted that it was the French corsairs and filibusters who were the fastest to modernize the musket, turning it into an effective melee weapon. First, the barrel of the weapon was shortened. A little later, even double-barreled samples appeared, allowing you to make a quick double shot. For two long centuries, the pirate musket, along with curved knives and sabers, became a symbol of pirate valor and courage. The main difference between the weapons used in the navy and the muskets of line regiments was their weight. Starting from the 17th century, lightweight models of muskets appeared. The caliber and length of the barrel have decreased slightly.

Now a strong and strong person could handle weapons alone. Basically, all the significant changes to the design were made by the Dutch. Thanks to the efforts of Dutch military leaders, the rebel armies received new types of firearms. For the first time, muskets became lighter, which provided troops with better mobility. The French, during the War of the Spanish Succession, also managed to contribute to the design of the musket. It is their merit that the butt of the weapon has become flat and long. The French were the first to install bayonets on muskets, giving soldiers additional offensive and defensive capabilities. The new regiments began to be called Fusiliers. The need for the services of pikemen disappeared. The armies received a more orderly battle formation.

The merit of the French is that they equipped the musket with a battery lock, making the French musket the most modern and effective firearm at that time. In this form, the musket essentially lasted for almost a century and a half, giving impetus to the appearance of smoothbore guns.

Musket as part of history and culture

By and large, it was with the musket that the development and improvement of small arms throughout the world began. On the one hand, the musket gave rise to shotguns, rifles, carbines, machine guns and machine guns, and on the other hand, short-barreled weapons like pistols and revolvers. That is why these ancient weapons exhibits are part of history.

On the other hand, muskets are a cultural and collectible value. Having an antique weapon can be the pride of a true amateur collector. In addition, some examples are decorated with precious metals and stones, which further increases their cultural significance.

The matchlock was invented around 1430 and made gun handling much easier. The main differences in the design of the new weapon were as follows: a predecessor of the modern trigger appeared - a serpentine lever located on the stock of the gun, with the help of serpentine the wick was activated, which freed the shooter's hand. The seed hole was moved to the side so that the fuse no longer covered the target. On later models of matchlock guns, serpentine was equipped with a latch and a spring holding it, a powder shelf for priming appeared, which later became closed, there was also a version of matchlock guns, in the design of which the trigger was replaced by a trigger button. The main disadvantage of matchlock guns was their relatively low resistance to moisture and wind, a gust of which could blow away the primer; moreover, the shooter had to constantly have access to an open fire, and in addition, the smoldering carbon deposits left after the shot in the barrel bore threatened to instantly ignite the loaded gunpowder. Thus, loading a matchlock gun from a powder flask with a large amount of gunpowder became quite dangerous, and therefore, in order to protect shooters from serious burns, cartridge belts were introduced, equipped with containers containing a smaller amount of black powder than before - exactly as much as was necessary to fire a shot.

The appearance of the first muskets

A musket is a long-barreled gun with a matchlock. This first mass-produced infantry firearm appeared earlier than anyone else among the Spaniards. According to one version, muskets in this form originally appeared around 1521, and already in the Battle of Pavia in 1525 they were used quite widely. The main reason for its appearance was that by the 16th century, even in the infantry, plate armor had become widespread, which did not always make its way out of the lighter culverins and arquebuses (in Rus' - “arquebuses”). The armor itself also became stronger, so that arquebus bullets weighing 18-22 grams, fired from relatively short barrels, were ineffective when fired at an armored target.

Matchlock musket and everything needed to load and fire it

Thanks to the production of granular gunpowder, it became possible to make long barrels. In addition, granular powder burned more densely and evenly. The caliber of the musket was 18-25 mm, the weight of the bullet was 50-55 grams, the barrel length was about 65 calibers, the muzzle velocity was 400-500 m/s. The musket had a long barrel (up to 150 cm) and a short butt with a cutout for the thumb in cervix The total length of the weapon reached 180 cm, so a stand was placed under the barrel - a buffet table. The weight of the Musket reached 7-9 kg. Due to the high recoil, the butt of the musket was not pressed to the shoulder, but was kept suspended, only by leaning the cheek against it for aiming. The recoil of the musket was such that only a physically strong, well-built person could withstand it, while the musketeers still tried to use various devices to soften the blow to the shoulder - for example, they wore special stuffed pads on it.

Loading was carried out from the muzzle of the barrel from a charger, which was a wooden case with a dose of gunpowder measured for one shot. These charges were suspended from the shooter's shoulder belt. In addition, there was a small powder flask - natruska, from which fine gunpowder was poured onto the seed shelf. The bullet was taken from a leather pouch and loaded through the barrel using a ramrod. The charge was ignited by a smoldering wick, which was pressed by the trigger against the shelf with gunpowder. Initially, the trigger was in the form of a long lever under the butt, but from the beginning of the 17th century. it took on the appearance of a short trigger. Recharging took an average of about two minutes. True, already at the beginning of the 17th century there were virtuoso shooters who managed to make several unaimed shots per minute. In battle, such high-speed shooting was ineffective, and even dangerous due to the abundance and complexity of loading techniques for a musket: for example, sometimes the shooter in a hurry forgot to remove the ramrod from the barrel, as a result of which it flew towards enemy battle formations, and the unlucky musketeer was left without ammunition. In the worst case, when loading a musket carelessly (an excessively large charge of gunpowder, a loose bullet seating on the gunpowder, loading with two bullets or two powder charges, and so on), ruptures of the barrel were not uncommon, leading to injury to the shooter himself and those around him. In practice, the musketeers fired much less often than the rate of fire of their weapons allowed, in accordance with the situation on the battlefield and without wasting ammunition, since with such a rate of fire there was usually no chance of a second shot at the same target.

Musket matchlock

The low rate of fire of these weapons forced the musketeers to line up in rectangular squares up to 10-12 rows deep. Each row, having fired a volley, went back, the next rows moved forward, and the rear ones reloaded at that time. The firing range reached 150-250 m. But even at this distance, hitting individual targets, especially moving ones, from a primitive smooth-bore musket, devoid of sighting devices, was impossible, which is why the musketeers fired in volleys, ensuring a high density of fire.

Improvement of matchlock muskets

Meanwhile, in the 17th century, the gradual withering away of armor, as well as a general change in the nature of combat operations (increased mobility, widespread use of artillery) and the principles of recruiting troops (a gradual transition to mass conscript armies) led to the fact that the size, weight and power of the musket over time began to be felt as clearly redundant.

In the 17th century muskets lightened to 5 kg with a rifle stock appeared, which were pressed to the shoulder when fired. In the 16th century, a musketeer relied on an assistant to carry a bipod and ammunition; in the 17th century, with some lightening of the infantry musket and a reduction in the caliber and length of the barrel, the need for assistants disappeared, and then the use of bipods was abolished. In Russia, muskets appeared at the beginning of the 17th century with the creation of “regiments of a foreign system” - the first regular army, formed on the model of European musketeer and reitar (cavalry) regiments and until Peter I existed in parallel with the Streltsy army, armed with arquebuses. The muskets in service with the Russian army had a caliber of 18-20 mm and weighed about 7 kg. At the end of the 17th century, for use in hand-to-hand combat (still remaining the decisive type of combat between infantry and cavalry), the musket was given a baguette - a cleaver with a wide blade and a handle inserted into the barrel. The attached baguette could act like a bayonet (the name “baginet” or “bayonet” remained behind bayonets in various languages), but it did not allow firing and was inserted into the barrel immediately before the shooters entered hand-to-hand combat, which noticeably increased the time between the last salvo and the ability to act with a musket as a bladed weapon. Therefore, in the musketeer regiments, some of the soldiers (pikemen) were armed with long-pole weapons and engaged in hand-to-hand combat while the riflemen (musketeers) were adjacent to the baguettes. In addition, with a heavy musket it was inconvenient to deliver long piercing attacks necessary in a battle with a mounted enemy, and when attacking cavalry, pikemen provided the shooters with protection from saber attacks and the ability to shoot point-blank at the cavalry. In the second half of the 17th century. This type of weapon throughout Europe was gradually replaced by military guns (fusees) with a flintlock.

Characteristics: Weapon length: 1400 - 1900 cm; Barrel length: 1000 - 1500 cm; Weapon weight: 5 -10 kg; Caliber: 18 - 25 mm; Firing range: 150 - 250 m; Bullet speed: 400 - 550 m/s.

Muzzle-loading weapons of the past - muskets, squeaks, fuses - did not have high accuracy and rate of fire, but were incredibly deadly, any wound threatened death or injury. Moreover, every major improvement in weapons led to a change in military tactics, and sometimes to a change in the military paradigm.

It is believed that handguns appeared in the 14th century simultaneously with artillery. The first samples were essentially the same cannons and bombards, only reduced so much that they could be fired from hand. They were called that - hand cannons. Structurally, these were bronze or iron pipes with a tightly sealed end and a pilot hole near it. Short trunks were laid on rough stocks, similar to elongated logs. Sometimes, instead of a stock, a long metal pin stuck out from the sealed end of the pipe, by which the weapon was held. The shooter aimed it at the target and ignited the gunpowder with a smoldering wick or a red-hot rod (often two people were involved in this process).

For almost two centuries, handguns did not provide any advantages. Bulky and inconvenient “hand cannons” were inferior in rate of fire to bows and crossbows - a good archer could shoot up to 12 times in a minute. The firearms operator spent several minutes on just one shot. The bullets of the first guns were not superior in penetration to crossbow arrows. In the second season of the documentary series Deadliest Warrior, an experiment is shown: a bullet fired from six meters from a modern replica of a Chinese handgun from the Ming Dynasty ricochets off a musketeer's shell, leaving only a dent on it.

Everything changed in the 15th century thanks to large-caliber muskets that fired bullets weighing 50-60 grams - they were guaranteed to hit a knight in armor. By the way, the term “musket” (like most other names for muzzle-loading weapons) is conditional. This was the name given to both heavy matchlock guns of the 15th-16th centuries and guns with a percussion flintlock of the 17th-19th centuries.

No matter how primitive early firearms were, they revolutionized military affairs: skilled and strong professional warriors soon found themselves powerless before the barrel of a musket. Historians consider the Battle of Pavia in 1525 between the French and Spaniards to be a turning point - it is called the last battle of the Middle Ages. It was then that firearms showed unconditional superiority over knightly cavalry. From that time on, the musket became the main weapon of the infantry, its tactics changed, and special musketeer units were created.

Matchlock guns of the 15th-16th centuries are still slow and cumbersome, but they acquire more or less familiar features; the wick is no longer brought to the ignition hole manually - it is mounted on a snake-like serpentine lever, activated by something like a trigger. The ignition hole is shifted to the side, next to it there is a special seed shelf on which gunpowder is poured.

And muskets and arquebuses are unusually deadly - a hit from a heavy or soft bullet almost always leads to death or severe injury - a soldier wounded in an arm or leg, as a rule, lost a limb.

But even the most advanced matchlock muskets are too inconvenient - the shooter thought more about how to ignite the gunpowder, and not about how to aim more accurately. The wick easily went out in bad weather, matches and lighters had not yet been invented, and it was impossible to quickly light the wick using a flint in case of a sudden alarm. Therefore, for the sentries, the wick was constantly smoldering, hidden in a special wick, wound on the butt of a musket or directly on the musketeer’s hat. It is believed that the guards burned out five to six meters of wick during their night shifts.

The wheel lock, known since the 15th century, slightly improved the situation. In it, a spark for igniting gunpowder on the seed shelf was struck using a rotating wheel with a notch. Before shooting, it was wound up with a key, like a music box, and when the trigger was pressed, it rotated, while at the same time a holder with a fixed piece of pyrite was pressed against it from above. Several engineers claim the authorship of the wheel lock; in particular, drawings of such devices are in the work of Leonardo da Vinci called Codex Atlanticus.

Although the wheel lock was superior to the wick lock in reliability, it was too capricious, complicated (they were made by watchmakers) and expensive, and therefore could not completely replace the serpentine with a smoldering wick. In addition, almost simultaneously with the wheel lock, a much simpler and more advanced percussion flint lock appeared - it is also called percussion, battery, or cross-cut. In it, a trigger with a flint hit a metal plate-chair, striking sparks, and at the same time a shelf with seed gunpowder opened. It flared up and ignited the main charge in the barrel.

Historians believe that the impact lock was invented in the Middle East. In Europe, the Spaniards were the first to use this scheme, and the French brought it to perfection. In 1610, gunsmith Maren Le Bourgeois combined the best features of different models and created the so-called French battery lock, which until almost the middle of the 19th century was the basis of handguns in Europe, the USA, and many countries of the East (not all, in Japan until the last quarter of the 19th century matchlock guns were used for centuries). By the 17th century, the final appearance of the flintlock gun had developed - a total length of about one and a half meters, a barrel of up to 1.2 meters, a caliber of 17-20 millimeters, weight - four to five kilograms. Everything is approximate, because there was no unification in production.

In addition to classic muskets, the military was armed with hand-held mortars for firing grenades and short blunderbusses with thick bell-shaped barrels from which they fired chopped lead, nails or small pebbles.

Perhaps the most famous flintlock weapon is the British land musket of 1722, nicknamed the Brown Bess. The wooden stock of the musket was brown, and the barrel was often covered with the so-called “rusty” varnish. “Dark Bess” was used in Britain itself, in all its colonies and was in service until the middle of the 19th century. This weapon did not have any outstanding characteristics, but gained its fame due to its wide distribution. The singer of British militarism and colonialism, Rudyard Kipling, even dedicated one of his poems to the brown musket - it is called Brown Bess. In the 1785 British Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, the expression “to embrace Dark Bess” means “to serve as a soldier.”

Experts call the French musket of 1777 the best flintlock gun. By that time, the engineer and fortification master Marquis Sebastien Le Prêtre de Vauban had improved the flintlock and invented the bayonet tube, which made it possible to shoot with a fixed bayonet - before that the bayonet was inserted into the barrel. With this gun, French infantrymen went through all the wars of the Revolution and the Empire. A shotgun with a Vauban lock was almost immediately adopted by all European armies. The Russian musket of the 1808 model was essentially a copy of the French gun with a slightly modified caliber.

The impact lock and development of the loading algorithm have significantly increased the rate of fire of muzzle-loading shotguns. Historians claim that 17th-century Prussian infantry fired up to five shots per minute with four reloads, and individual riflemen fired up to seven shots with six reloads.

To speed up loading, gunpowder, wad and bullet were combined in one paper cartridge. The French manual for loading weapons included 12 commands. Briefly, the process looked like this: the soldier put the trigger on the safety cock, opened the cover of the priming shelf, bit into a paper cartridge, poured some of the gunpowder onto the shelf, and then closed it. He poured the remaining gunpowder into the barrel, sent a paper cartridge with a bullet there - the paper served as a wad, nailed the bullet with a ramrod, then cocked the hammer. The gun was ready to fire.

By the way, the paper cartridge played a cruel joke on the British - it is believed that it was this that served as the reason for the sepoy uprising of 1857-1859 in India. In February 1857, the 34th Bengal Regiment of Native Infantry heard a rumor that the casing of the new paper cartridges was impregnated with either cow or pork fat. The need to bite such cartridges offended the religious sentiments of Hindus and Muslims. One of the native soldiers announced that he would not bite the cartridge, and when the regimental lieutenant arrived to investigate the incident, the native shot at him, wounding his horse.

But even the most advanced musket was not accurate - hitting a target one meter square from a hundred meters was a very good result. Targeted salvo fire was carried out at distances of 50-100 meters - it was believed that it was impossible to hit the enemy line further than 200 meters. Most armies allowed soldiers to fire three to five practice rounds to become familiar with the loading process. Everything else is in battle.

But the techniques of volley firing were worked out to perfection - to reduce the time intervals between volleys, a formation of riflemen from several ranks was used. The first rank fired a volley, went back to load guns, the second rank took its place with loaded muskets, after the volley it gave way to the third rank, etc. There were techniques for shooting in three ranks at once: the soldier in the first rank stood half-turned, the next one remained in place, the third took a step to the right.

The first examples of rifled weapons date back to the 15th century - in the arsenal of Turin there is a rifled gun from 1476. Already by the first quarter of the 16th century, high-quality rifled guns were available in various European countries, primarily in Germany. But these were isolated samples, available only to the rich.

Early rifled weapons are sometimes called a "premature invention", in the sense that the level of technological development at the time precluded their widespread use. The first flintlock revolvers are also among the same premature inventions - one of the oldest samples dates back to 1597 (Colt’s first revolver appeared in 1836), and in the Kremlin Armory there is a revolver arquebus from 1625.

The accuracy of the first rifled gun made such a strong impression on contemporaries that it provoked a religious dispute. In 1522, a Bavarian priest (according to other sources, a warlock) named Moretius explained the accuracy of rifled weapons by saying that the demons swarming in the air cannot stay on rotating bullets, because there are no devils in the rotating heavens, but there are plenty of them on Earth. Moretius' opponents insisted that the demons just like everything that rotates, and they probably direct the spinning bullet.

An experiment conducted in the German city of Mainz in 1547 put an end to the dispute. First, plain lead bullets were shot 20 times at targets from a distance of 200 yards, then another 20 shots were fired with blessed silver bullets with crosses inscribed on them. Half of the lead bullets hit the target, while the silver ones missed. The answer was obvious. Church authorities banned the “devilish weapons,” and frightened townspeople threw their rifles into the fire.

True, those who could afford rifled weapons continued to use them. But more than three hundred years passed before, by the end of the 17th century, they created a rifled gun suitable for relatively mass armament of infantry. It was only in the second half of the 19th century that rifled muzzle-loading rifles replaced classic muskets from the army.

Manufacturing technology

Making a working musket at home is extremely difficult and unsafe.

It should be noted right away that making a working firearm is not only a complex, but also a dangerous process. Especially when it comes to early models, which include the musket.

Even factory samples of such weapons often led to injuries, jamming and bursting right in the hands of the shooter, so it is better to limit ourselves to creating a model without going into the intricacies of the functioning of the combat prototype.

Material selection

The best material for making a musket model with your own hands is wood. And so that your weapon does not lose its attractive appearance, becoming distorted under the influence of moisture, the workpiece should be dried for a year. To do this, you must follow these recommendations:

- Cut off a branch or trunk.

- We paint the cuts on both sides. For this, varnish, paint or adhesive can be used. This approach is necessary so that the wood dries more evenly and internal cracks do not appear in it.

- Now the workpiece is placed in a dry, dark place where sunlight should not penetrate.

- After a year, you can carefully remove the bark from the workpiece, after which it should dry for about another week.

- Now you should cut the branch in half, after which you can begin to directly create the musket.

Model assembly

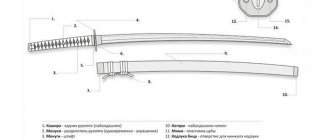

Exploded model of a musket

In addition to a block of wood, to make a model of a musket you will need a small piece of pipe and strong wire. It is advisable to choose a not very thick chrome-plated pipe or, on the contrary, one covered with rust (this approach will allow you to create a model with a touch of antiquity).

First we make the handle. To do this you need to follow these steps:

- We find a picture of a musket on the Internet, which will become our model.

- Carefully transfer the pen of the product to a sheet of paper. In this case, you must try to maintain all proportions.

- Cut out the resulting pattern.

- We apply the pattern to a wooden beam and securely fasten it to it.

- We draw the contours of the future workpiece.

- Using a utility knife, we remove excess layers of wood until we get a handle that matches our pattern.

- The last stage is surface treatment with sandpaper. At this stage, you can hide small irregularities that were made earlier. As a result of such processing, the workpiece should become perfectly smooth.

Advice! To protect a wooden surface from moisture, it is advisable to soak it in oil, varnish or paint.

After you have finished making the handle, you should attach a pre-prepared tube to its upper part. In the original muskets, the barrel is slightly “recessed” into the handle, so a small recess should be made in it to securely fix the elements.